Essays on the Chapter House

Uses and Customs

The Salisbury chapter house, a consecrated building, was second only to the cathedral in importance. It enjoyed daily use until the Reformation, when Henry VIII ordered the dissolution of monasteries. Up to that time, following the Sarum Use, the cathedral community walked in procession to the chapter house every morning after prime-song. There the daily ritual continued as prescribed by the consuetudinary of St. Osmund known as De Officiis Ecclesiasticis Tractatus.

Salisbury chapter house

Chapter house consecration cross, now on south transept

East wall of chapter house, bishop's seat

Plan of chapter house

The dignitaries and canons took the seats permanently assigned to them by the Tractatus. When present, the bishop occupied a central seat along the east wall, with the dean, chancellor, and sub-dean on his left. On either side the members of the cathedral community took their places according to their rank in the cathedral hierarchy, and also in order of rank, the boy choristers stood on either side of the pulpitum.

The service in capitulum began with the reading of the first lesson from Salisbury's martyrologium by the boy chorister who had been designated as reader for the week. After the lesson, he read the obits for the day, if any. Then, standing behind him, the priest blessed the souls of those deceased and completed the liturgical ritual for remembering the dead. The service continued with the second lesson, again delivered by the boy reader, lessons usually taken from the writings or homilies of Haymo, a ninth-century scholar in Charlemagne's court. The benediction then concluded the daily service. Next, stepping down from the pulpitum, the boy read the tabula, the 'brede bord' or common table containing the roster of daily and weekly assignments set by the precentor. It was, and still is, his duty to designate the places of the canons and boys in processions and in the choir.

Rituals in the chapter house also included acknowledgements by members of the community of any derelictions in their duties followed by the setting of their punishments. The Institutio Osmundi was quite specific about discipline, and any recalcitrant who did not reform after admonishment by the dean had then to prostrate himself in capitulo to receive his punishment.

In addition, the chapter house was the locus for a variety of other functions. There the chapter met to conduct business, but those meetings remained distinct from the daily ritual and, unlike the latter, only the canons and dignitaries attended, not the entire cathedral community. The building was also used for archepiscopal visitations and the bishop's synodal meetings. The tenets of the church were upheld and enforced not only in meetings of the chapter, but also in the visitations and at the bishops' convocations. In addition, elections of bishops and deans took place in the chapter house, and their installations and the attendant processions formed there. The great dignity accorded the two offices required the assembled to stand whenever either official entered the chapter house or the choir.

And finally, on Maundy Thursday one of the most solemn rituals of the liturgical year took place in the chapter house. After evensong and the ritual washing of the altars, the procession repaired to the chapter house for the Mandatum, or washing of feet, and for the potum caritatis, or loving cup received first by the bishop and then administered to the clergy and others present.

After figuring largely in the daily and occasional rituals from the time of its completion until the Reformation in the sixteenth century, the Salisbury chapter house then stood idle and neglected for the next three centuries.

Design

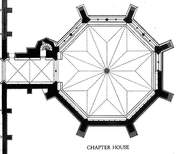

The visitor approaches the chapter house through a doorway off the east walk of the cloister. This leads into a two-bay vestibule, or foyer. An inner doorway opens onto the main chamber from the foyer (fig. 1). The octagonal chapter house (fig. 2) derived its proportions and design from the earlier building at Westminster completed in 1253. The building agreement for Salisbury may have specified that the chapter house 'be like' the one at Westminster, a common clause in such contracts in the Middle Ages. Both buildings measure 58 feet across, but the height of the Westminster vaults, 54 feet, exceeds Salisbury's vaults by two feet. As at Westminster, the vaults spring from a high central column surrounded by eight slender, detached Purbeck marble shafts trisected by molded bands or annulets (fig. 3). Although the parentage of the building is beyond dispute, variations in detail avoided a slavish copy.

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 3

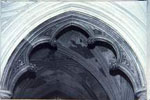

Clockwise around the octagon, beginning and ending at the doorway in the western bay, a plinth approached by one step forms a continuous base for the fifty-one seats of the canons. In the eastern bay an extra step elevates the seats of the dignitaries above the others (fig. 4). The seats of the eastern bay are not only higher but also more deeply recessed than the others. Detached, quatrefoil, Purbeck marble shafts support the continuous blind arcade, and cinquefoiled, broken arches define and frame the canons' seats.

Figure 4

Human heads, animals, and birds invade the richly varied, stiff-leaf foliage of the capitals of the arcade (fig. 5). Heads, remarkable for their quality and variety, act as label stops for the hood molding of the arches (fig. 6). Some caricatured, others idealized, classicized, or realistic, the heads represent all walks and stations of life, from kings, queens, and princes to friars, nuns, priests, merchants, damsels, and laborers. Drawings dated 1802 by John Carter, one time artist for the Society of Antiquaries of London, have preserved a record of the heads and capitals in enough detail to show their condition before the nineteenth-century restorations (fig. 7). And finally, sixty narrative scenes from the Old Testament, the sculptural treasure of the building, fill the spandrels of the blind arcade. A full list and photographs of the sixty scenes are accessible from the Contents bar at left.

Figure 5

Figure 6

Figure 7

Above the arcade, traceried windows of four lancets stretch across each bay to create the illusion of a wall of glass (fig. 8). Two quatrefoiled oculi occupy the headings of enframing arches that divide the lancets into pairs. Above, in the enclosing arch that spans the bay, a large, octafoiled oculus crowns and dominates each window (fig. 9). The cusps of the octafoils terminate in another series of heads notable for quality and variety (fig. 10). The design of the windows has a closest affinity with tracery found in the clerestory at Lincoln and in the south aisle of the choir at Beauvais. But Lincoln, Beauvais, and Salisbury are all indebted to the ultimate source of the pattern, the clerestory windows in the nave at Amiens.

Figure 8

Figure 9

Figure 10

In order to accommodate the fenestration of the western bay of the chapter house to the high rising arch of the entrance, the designer resorted to an awkward device reminiscent of the arrangement in the entrance bay of the Westminster chapter house. Above the arch of the Salisbury doorway, an upper tier of blind arcading, trefoiled rather than cinque-cusped, reduces the height of the lancets in the window above by approximately one-third (fig. 11).

Figure 11

The Salisbury design maintains the self-sufficiency of the bay units, the vertical linkage of the zones, and the assimilation of mural surfaces into the windows -- inseparable principles of the French Rayonnant system. Yet despite the universally accepted and striking similarities of the Salisbury and Westminster buildings, the Salisbury design underwent a subtle anglicizing of the vocabulary of the French Rayonnant style. A series of modifications increase our awareness of the mass of the walls and add to the plasticity of mural surfaces. The designer at Salisbury began to subvert the 'flat skeletal treatment (that prerequisite of thinness)' that characterized the Rayonnant style, which, as Jean Bony has put it, was achieved by the rational and systematic elimination of all substantially plastic forms. In effect, even though the designer of the Westminster chapter house introduced the French style as a coherent system, the mutants visible at Salisbury run counter to it.

All critics agree that the chapter house forms an architectural entity with the cloister. Apparently both belonged to the program anticipated by Bishop Walter de la Wyle's gift of land in 1263 to enlarge the cloister compound to the south. Francis Price, the eighteenth-century carpentarius of the cathedral, made the telling observation that the masonry and buttresses of the bell tower (destroyed), cloister and chapter house differed from those of the cathedral, thus linking the three buildings technically. The different masonry implies that the cloister and chapter house were not part of the same campaign as the cathedral or by the same workshop. Indeed, Bishop Walter's deed of 1263 makes it clear that the cloister had not yet been constructed by that date. His gift stipulated that it was to 'be suitably embellished, conforming in design and material to the church of Salisbury, and the same...be nobly joined to our cathedral church.' The deed indicates that probably in the 1190s, provisions had been made and the area set aside when land in the valley was apportioned for the thirteenth-century cathedral complex.

Ornament and Dating

Without question, the plans for the cloister and chapter house were being formulated in 1263, and all critics agree that the king's new works at Westminster, especially the chapter house, influenced the design. But critics have not agreed on a date for the chapter house, and those proposed range from 1260 to 1280. Dendrochronology, the dating of timbers by counting tree rings, proved inconclusive, but favored a date in the 1260s. Those who support the early date base also their conclusions on the similarity of the Salisbury building to the Westminster chapter house built in the 1250s. Yet the halting progress of construction of the cloister walks is indicated not only by breaks in the masonry and changes in the profiles of the molded bases and capitals but also by a gradual change in the foliate style of the roof bosses from stiff leaf to recognizable naturalistic leaves and flora and then to undulating leaf forms. These characteristics argue for a campaign of construction extending over decades and the later date of 1280 for start of work on the chapter house.

In 1276, the king had granted the chapter permission to use stone from Old Sarum. Although spolia from that Norman cathedral complex can be found at the triforium level in the cathedral, in the cloister evidence of reused stone from Old Sarum first appeared on the exterior of the south wall in the southeast corner bay. The documented fund raising efforts in the seventies together with the king's grant seem to corroborate the chronology of construction in the cloister proposed by Nikolaus Pevsner. Basing his conclusions on stylistic changes in the foliage of the roof bosses, he observed that only the stiff-leaf type occurred on the bosses of the north walk, the first to be built. Along the east walk, the next one constructed, the bosses exhibit similar stiff-leaf forms, but a few botanically plausible leaves begin to intermingle in the southern bays of that walk, though much subordinate there to the overall patterns created by stylized foliage. Thereafter, the ratio of more naturalistic to stiff-leaf forms increases in the first seven bosses of the south walk.

The trend towards naturalistic representations of foliate forms for ornamental, not symbolic purposes originated in ca. 1240 in France, with Reims the focal point from which the style spread. In England naturalistic foliage appeared precociously at Lincoln, Westminster, and at Windsor in a few capitals and bosses, all dated between ca. 1240-1260. The style spread slowly and did not begin to flourish in England until ca. 1275. From then on through the last quarter of the thirteenth century the older, stiff-leaf forms persisted usually in diminishing proportions alongside naturalistic or 'pseudo-naturalistic' vegetal forms. (The term 'pseudo-naturalistic' applies to the recognizable leaves that do not replicate organic growth.) In the last decade of the century, botanical realism reached its apex in the rendering of the delicate, recognizable leaves on the capitals and moldings of the chapter house at Southwell Minster, justly celebrated for their exquisitely carved, botanically correct specimens of leaves, flowers, fruits, nuts, and berries. That last stage, fully realized in the Southwell chapter house ca. 1293, marked the moment before the introduction of undulating leaf forms which tended to undermine the realism. Along with that last change came a tendency to emphasize the overall pattern or composition at the expense of the individuality of each leaf. A concern with the overall design created by the distribution of leaves across the surface of the boss or capital is quite evident in the bosses of the chapter house at Wells, a building in progress in the 1290s and completed by 1307.

An interesting comparison exists between some of the foliate capitals at the entrance to the Wells chapter house and carved elements that have survived on the mutilated capitals of the colonnettes of the original central column from the Salisbury chapter house (fig. 1). (What remains of the column is now stored in the southwest corner of the cloister). The strongly articulated stems from which large maple leaves spring are distinctive characteristics which they share. Although arranged in two tiers on the capitals of the Wells chapter house entrance, the maple leaf forms there compare well with those of the central column -- the large leaves bridging the gap between the stiff leaf capitals and the only ones still legible.

Figure 1

In effect, the bosses of the east and south walks at Salisbury paralleled the trend in England from the mid-1270s on as the stiff-leaf foliage gradually yielded to pseudo-naturalistic flora. Then, in the bosses of the chapter house (fig. 2) we find more botanically accurate representations, and on the lintels of the arcade in the east bay of the octagon (fig. 3), we see beginnings of the concept of organic growth. Yet none of the bosses along the south walk equals the chapter house bosses in delicacy of form, depth of undercutting, intricacy of composition, and proliferation of pseudo-naturalistic forms. The carver seems to have refined his techniques and elaborated upon some designs that had already appeared in the south walk. The increased virtuosity of the carving suggests a progression from work on the south walk to work in the chapter house, but such an hypothesis would be tenuous were it not for the half-finished boss in the eighth bay from the east. The foliage on the eastern half of the boss is congruent with the stylized forms in the bays to the east, whereas the western half is in the undulating leaf style of the 1290s. That change of style is coupled with the discontinuous courses of masonry in the bay, further underscored by significant changes in the profiles of the molded capitals of the colonnettes between the seventh and eighth bays compared with those between the eighth and ninth bays. That interruption may mark the beginning of work on the chapter house. With the king's gift and technical evidence proposing 1276 as the terminus post quem for the first seven and a half bays and bosses of the south walk, the date of 1280 becomes credible -- a date proposed for the chapter house by the pennies from the earliest coinage in the reign of Edward I (Dec. 1279) found during the 1856 restoration when reinforcing or underpinning foundations of the chapter house. In addition, the consecration cross of the chapter house (fig. 4) compares closely with the pinwheel boss in the fifth bay of the south walk, a similarity suggesting that they were fairly close in date.

Figure 2

Figure 3

Figure 4

In the roof bosses of the chapter house, fanciful beasts, drolleries, and winged serpents with human heads and foliate tails inhabit and encircle the pseudo-naturalistic foliage. Again, above the blind arcade over the inner entrance, similar creatures undulate and intertwine, their tails terminating in both naturalistic and stylized leaves (fig. 5). The sinuous bodies of the serpents and the earthy antics of the 'babuineries' typify a trend well recognized in manuscripts that was also current in sculpture from 1275 to 1310. The period was distinguished by a veritable 'incursion of grotesques executed with vigor and naturalism...a profusion of "babuineries"...a term used to describe grotesques, dancers, jugglers, and small animals performing human acts.' William Burges, having seen the rim of the boss in the northwest bay from scaffolding, wrote: 'Each of three divisions into which it [the boss] is separated by ribs is occupied by a grotesque group of figures...respectively the armourers, musicians, and the apothecaries....The figures, although similar in style to those below, exhibit a vast difference in their execution, inasmuch as every feature is marked and distorted in the strongest manner. Indeed, concerning one group (viz., the musicians), the less said the better, for the artist has by no means confined himself within the bounds of decency.'

Figure 5

Grisaille and Inlaid Tiles

The literature has not achieved a consensus on the dating of either the glass or the tiles. In what is still the most authoritative study, Charles Winston concluded that the glass could not possibly be earlier than 1270-1280. Winston supported his dating with diagrams of the geometrical forms of the grisaille that overlap in depth. Basing his proposal on the heraldry, Canon Fletcher proposed a date of ca. 1280, but using the same criterion, Hugh Shortt proposed a date of 1268. N.H.J. Westlake thought the grisaille could be even later than 1280. His conclusion also rested on the complicated, overlapping geometrical forms in the windows and the presence of some foliage that overruns the limits of the geometrical patterns, both dominant characteristics of grisaille towards the close of the century. Neither of those later tendencies was in evidence in grisaille surviving from the 1250s and 1260s at Westminster. Westlake based his dating on comparisons with grisaille probably from the Westminster chapter house which he concluded had predated the Salisbury chapter house glass by about twenty years. Although the foliate designs compared well, at Westminster there was no overlapping of either geometric or foliate forms. Then, too, after close analysis of the grisaille panel from a window of the Salisbury chapter house in the Raymond Pitcairn collection and comparisons with other English grisaille, Jane Hayward, the late curator of medieval glass at The Cloisters, New York, concluded that the glass was made well into the 1280s. Most recently, though without any stylistic and technical analyses of the grisaille, the survey of English glass by Richard Marks suggested a date in the 1260s.

Dating of tiles also presents difficulties because even when documents provide dates for a building, the installation of the tiles may have occurred sometime after the documented construction date. Along with nineteenth-century drawings recording the patterns used in the chapter house, some tiles removed during the mid nineteenth-century restorations have survived (figs. 6 and 7). Many were relaid in the east bay of the north aisle of the church to pave an area nine by four feet. E. S. Eames proposed a date in the late thirteenth century for two of the designs and assumed they came from the kiln at Clarendon. We find among those preserved in the north aisle installation both the adorsed birds separated by a conventional tree with stiff leaf foliage, all set diagonally on the tile and what Eames described as 'four fleur-de-lys springing from the corners of a central square containing a pierced quatrefoil'. These and other chapter house patterns have been found in Wiltshire at Stanley Abbey (ca. 1280); Corsham Court (late thirteenth-century); the Queen's Chamber at Clarendon Palace (1250-1252); Britford; Ivychurch; St. Nicholas Hospital, Salisbury (completed in ca. 1245); Amesbury (ca. 1279), and in the muniments room of the cathedral, now the choir practice room, which critics generally date after the chapter house. Although that last lacks a precise date, most agree with a dating in the late thirteenth century. Until recently a wooden floor protected and completely hid the tiled pavement. Intact and unrestored, the floor replicates most, but not all of the designs from the chapter house.

Figure 6

Figure 7

Those various monuments establish a range of more than forty years for the occurrence of the same patterns, and would allow either 1265 or 1280 for dating the chapter house. But to judge from the loss of clarity in outlines, some of the wooden forms used to impress designs on the extant tiles from the chapter house had seen long service--a valid reason for dating the pavement towards the end of the period. Unfortunately, dendrochronology and the evaluation of glass and tiles have not dispelled uncertainties about the date of the chapter house.

In summary, in 1263 the deed by which Bishop Walter de la Wyle gave land to enlarge the cloister precinct specifically stated that the cloister was to 'be suitably embellished, conforming in design and material to the church of Salisbury.' That statement tells us unequivocally that the cloister had not yet been built. The bishop also enunciated his conservative attitude with respect to the cloister's design. He asked that it be constructed to harmonize with the stone and design of the cathedral, even as preference for visual unity and stylistic harmony had prevailed throughout the building of the cathedral over a forty-year period. This conservatism could explain the stylistic continuity in the design of the cloister and chapter house despite any protracted chronology of construction. Recently, Paul Williamson concluded that the evidence for a post-1279 date for the chapter house date was 'far from water tight.' He concluded that 'the closeness of the design to the Westminster chapter house, the practical necessity for a meeting place for the chapter, and the style of the head stops, the Purbeck marble stiff-leaf capitals and stained glass, all suggest an earlier date, perhaps in the 1260s.' His arguments restate in summary reasons others have given for dating the building in the 1260s.

Yet that conclusion does not take into account the more naturalistic foliate forms in the capitals in the eastern bay, the botanically plausible foliage in the bosses, geometric patterns in the grisaille that overlap in depth, or the most advanced molded profiles, none of which is compatible with a date in the 1260s. The same may be said for the Purbeck marble naturalistic foliate details of the inner portal, notably in the spandrels of the cinqfoiled arches and on volutes terminating the cusps of the foliage on the capitals (fig. 8). As for the label stops, stunning in their variety, those heads quite defy dating. They range from many that seem like portraiture to boldly caricatured male heads, idealized women's faces, and even include a classicized male head that suggests the artist's knowledge of sculpture from Antiquity (or perhaps French interpretations of it). Unlike the Purbeck heads in the cathedral, those in chapter house were carved in limestone by sculptors gifted with a remarkable and timeless talent. The most datable aspect would be the coiffures and headdresses, both male and female, which are typical of the last quarter of the century. Then too, the figure and drapery style in the Old Testament scenes show mannerist tendencies that reflect the Paris Court style. The style did not become truly exportable until the 1270s and was probably carried abroad by ivory carvings of that decade.

Figure 8

Decorative elements generally offer artists the greatest leeway to experiment and therefore tend to contain the most up-to-date and innovative details, as for example, the marginalia of manuscripts. Where the artists did not have to perpetuate established iconographical traditions, they enjoyed greater freedom of expression. Had the chapter house been completed by ca. 1265, the amount of naturalistic foliage we find there would have been extraordinarily precocious. The same would have been equally true of the most advanced molded profiles (found in the vaulting ribs) and the overlapping designs of the grisaille. When the fund raising efforts that did not begin until 1270 are also considered, it becomes as difficult to dismiss the 1279 date proposed by the pennies as it is to accept the earlier date of 1265. The accumulated evidence favors a date sometime after 1270 which is certainly not incompatible with the range of dates proposed by the analysis of the timbers, but differs from the estimated date suggested by averaging the results for all the beams sampled. Nevertheless, the date that work began and the year of completion still remain uncertain.

The second campaign involving the cloister and chapter house achieved two buildings that belong on the list of finest architectural achievements in the geometric phase of the Decorated style. They owe their harmonious proportions and visual unity to the plan formulated in ca. 1263. Yet to judge by breaks in the masonry coursing along the cloister walks and striking changes in the style of the roof bosses, the building campaign progressed slowly. Whether the pennies of 1279 from the reign of Edward I found beneath the foundations of the chapter house during the mid-nineteenth-century restorations provide the terminus post quem for the start of construction there, or the felling of the timbers provide a terminus ante quem, there can be no doubt about the protracted chronology of the second campaign.

Iconographical Program

Depleted in the sixteenth century by the removal of much of the glass, then marred by deliberate mutilation of the sculpture in the next century during the Civil Wars, the thirteenth-century program again suffered irretrievable losses in the early nineteenth century. Although no record of that work exists in the archives, vestiges of relief sculptures on both faces of the inner entrance were eliminated some time between 1802 and 1856. Nevertheless, with the aid of pre-restoration drawings, enough remains to enable us to reconstruct the original iconographical plan almost in its entirety, one perfectly suited to the uses and symbolic meaning of the building itself. That program encompassed the sculpture on both faces of the inner doorway, the sixty Old Testament scenes in the spandrels of the wall arcades, the heraldic devices set into the grisaille in the lancets of the eight bays, and the figurate glass in the tracery above those lights.

On the west or vestibule side of the doorway, the inner order of the enframing arch contains fourteen niches with statuettes depicting fourteen Virtues and Vices in combat (figs. 1 and 2). Beneath trefoiled canopies surmounted by villes sur arcatures, elegant and erect figures of the Virtues, having conquered the Vices, inflict hideous and appropriate punishments on them. Damages and losses to those figures recorded in pre-restoration drawings were repaired in the mid-1850s. Fortunately, the surviving polychromy gives assurance that the hand of the restorer was fairly restrained, making these figures the best preserved and least restored of any in the building.

Figure 1

Figure 2

Unfortunately, no traces of the figurate sculpture below them in the tympanum have survived. By the mid-nineteenth century, when William Burges made his notes on condition, the two figures that originally occupied the central niche had completely disappeared. But a pre-restoration drawing of 1802 recorded vestiges of the sculptures still visible in the first decade of the century (fig. 3). The sketch depicts two badly damaged, seated figures symmetrically placed beneath the five-cusped arch and supported by a wide foliate socle (the latter still extant). The composition evokes the traditional imagery of the Coronation of the Virgin. The figure on the left represents the Virgin who is seated on Christ's right. His gesture provides the crucial evidence for establishing the iconography. The stump of his raised right arm is reaching towards the Virgin's head. More than a century earlier, the imagery for the Triumph and the Coronation of the Virgin had evolved from the Feast of the Assumption. After her bodily assumption into Heaven, Christ had elevated her to share his throne. In the sketch, he is placing the crown on her head to claim her as his bride. Christ and his bride, Maria Ecclesia, a type for the Church, would rule under the New Law through all eternity. Thus, the information preserved in the drawing has overcome the lacuna that heretofore presented a major obstacle to reconstructing the thirteenth-century program.

Figure 3

On the interior face of the same doorway, the loss of the sculptures formerly in the niches of the blind arcade above the entrance also created a problem in reconstructing the original program (fig. 4). Noticing iron crampons used for securing statues in the four full-sized niches of the arcade, Burges posited the loss of four full-length statues, even though no other traces remained. Among the many early views of the east face of the inner entrance, only two support the hypothesis. In addition to pencilled notes recording red and green grounds in the niches seeded with white floral motifs, one sketch contains the outlines of damaged elements beginning approximately at the level of the capitals flanking the outer niches. There a series of indefinite scribbled lines resemble those the artist, John Carter, consistently used to indicate mutilated areas when sketching the Old Testament scenes (figs. 5 and 6). Validating Burges's hypothesis, the scribbles apparently represented vestiges of lost figures.

Figure 4

Figure 5

Figure 6

The disappearance without a trace of the four figures in the arcade above the east face of the entrance seriously hampers the reconstruction of the original program, and proposals about their identities must remain speculative. Nevertheless, enough survives of the remaining sculpture and the thirteenth-century figurate glass to propose an iconographically coherent program.

Early nineteenth-century drawings and prints authenticate fragments of thirteenth-century carving still extant on the east, or interior face of the inner entrance. Remnants include a quatrefoiled oculus containing the symbols of the four Evangelists. Elegant and elongated figures, the Angel of Matthew, the Lion of Mark, the Ox of Luke and the Eagle of John occupy the spandrels formed by the cusps (fig. 7), but no traces of the central figure in the oculus had survived. Yet the nineteenth-century figure of Christ in Majesty now filling the quatrefoil within the oculus was correctly construed from the presence of those symbols. Directly below in the angle formed by the springing of the two arches of the doorway, the small mutilated demi-figure of an angel is emerging from a cloud formation. Although stylistically incongruous, the restoration continues an iconographical tradition rooted in art of the preceding centuries. The enframing quatrefoil, rather than an almond shaped mandorla, supplies a particularly English flavor. The damaged demi-angel in the spandrel below Christ still retains a vestige of his original attribute. Despite sanding by the restorer to smooth broken edges, the bowl of a censer is discernable somewhat to the left and forward of the cloud formation. The attribute associates the figure with the angel of the Apocalypse, who, when the seventh seal was broken, 'came and stood before the altar, having a gold censer; and there was given him much incense, that he could offer the prayers of all the saints upon the golden altar which is before the throne of God (Apoc. 8:3).'

Figure 7

The motif of a demi-angel emerging from clouds recurred again in the tracery of the chapter house windows. Sixteen medallions of painted glass originally located in the quatrefoils above the lancets represented an angel choir. Now considerably restored, ten surviving roundels are scattered in the composite windows of medieval glass in the western parts of the nave and side aisles (figs. 8, 9, and 10). The angels either gesture and/or carry an attribute associated with the apocalyptic Second Coming of Christ: the palm and crown of the martyrs, a crescent moon, a harp or lyre, a book, and censers.

Figure 8

Figure 9

Figure 10

Although the theme of the Last Judgment dominated the iconography of the thirteenth-century programs at Lincoln, the apocalyptic Second Coming was the preferred theme at Salisbury where we find three thirteenth-century versions in all. One was in the vault paintings of the eastern transepts of the cathedral. It accompanied the Second Coming painted in the vaults of the choir. The second occurred in the decimated sculptures of the west facade. There the eagle perched on a banderole in the central gable, the symbol of St John the Evangelist, was correctly identified as early as 1897, but its significance, a reference to the apocalyptic Second Coming, had been generally ignored. At Wells, the eagle perched on the lectern of the angel of the Apocalypse in a quatrefoil that precedes a series of New Testament scenes stretching across the facade to the north informed Brieger's interpretation of the program as the New Jerusalem of the apocalyptic vision. At Salisbury, although less complete, both the organization of figures in aedicules and the program of the west front was derived from Wells. Not all of the aedicules were ever filled, and today most of the statues date from the nineteenth century. A recent restoration of the west facade has placed newly carved statues in some of the niches.

The third apocalyptic Second Coming occurs in the chapter house. Since there was never any representation of the Resurrected Dead or of the Weighing of Souls in either the glass or sculpture, we may reasonably conclude that the angel choir in the tracery of the windows accompanied Christ of the Second Coming enthroned in majesty in the quatrefoil above the entrance. Collectively the demi-figures represented 'the voice of many angels' heard around the throne (Apoc. 5:11). The Old Testament cycle in the spandrels, beginning with Creation and ending with the Giving of the Old Law, accompanies the New Testament Christ of the doorway. Because the series is essentially narrative in character rather than typological, its aggregate meaning is inherent in and emphasized by Moses receiving the Law of the terminal scene. In the context of the chapter house program, the Old Testament cycle symbolizes the Old Law in apposition to Christ of the Second Coming who embodies the New Law. Christians approached and understood the Old Testament through the New, which was the gospels. In the words of the Apostle Paul, 'the end of the law is Christ (Romans 10:4),' and as a corollary, the path by which one goes to Christ is the Law. Those interpretations put the emphasis on Salvation through moral obedience--an apt emphasis for a building where the New Law was administered and discipline enforced, and where prayers were said daily for the souls of the dead. In addition, the imagery and symbolism inherent in many of the Old Testament scenes refer explicitly to Salvation through the Church.

Any reconstruction of the program must also account for the fragments of glass portraying kings and ecclesiastics--remnants of figurate glass that once filled the tracery of the windows--as well as the heraldic shields formerly interpolated into the grisaille of the lancets. The sole surviving medallion from one of the oculi at the headings of the windows pictures a bishop and a king, each in an aedicule surmounted by a turreted architectural motif (fig. 11). Three more extant figurate panels from the Salisbury window tracery depict two bishops and a king (fig. 12). Those kings and ecclesiastics have their counterparts in the figures in aedicules of the west screen at Wells cathedral. Begun in 1220, the Wells facade was probably completed by ca. 1260, up to and including the frieze of the Resurrected Dead. (The sculpture of the stepped gable surmounting the screen-like facade dates from the fifteenth century.) Stretching across the facade and turning the corners of buttresses and towers, niches or aedicules ranged in three tiers frame figures of kings, queens, bishops, clerics, deacons, saints, knights, martyrs, and prophets, but most of the figures are no longer identifiable. In his compelling interpretation of the Wells west screen, Brieger proposed that the sculptural ensemble represents the Church Triumphant, the Heavenly City revealed to St. John of Patmos (Apoc. 21:2-3): 'And I John saw the holy city, the New Jerusalem, coming down out of Heaven from God, prepared as a bride adorned for her husband. And I heard a great voice from the throne saying: Behold, the tabernacle of God is with men.' We can carry Brieger's interpretation further. The kings, bishops, saints, warriors, et al., would be those who kept the New Law and 'washed their robes in the blood of the Lamb: that they may have a right to the tree of life, and may enter in by the gates to the city (Apoc. 22:14).'

Figure 11

Figure 12

In extending Brieger's interpretation of the vast sculptural program at Wells, we should also take into account the Virgin and Child in the tympanum of the central portal. They refer to the First Coming by which the Church was established. The Virgin's foot resting on the basilisk, a metaphor for evil, imbues her figure with the special meaning of Maria Ecclesia, and signifies the triumph of the Church over evil. Directly above, under a trefoiled arch, the scene of the Coronation of the Virgin, also equated with the Church Triumphant, explicitly represents Maria Ecclesia as the Bride of Christ. Again the figures are treading on the symbols of evil: Mary upon the adder, Christ upon the basilisk. A third ensemble, the figures in the archivolts enframing the Virgin and Child below, reinforce the metaphor of the Church Triumphant. These badly mutilated, standing female figures have been identified as Virtues. Having overcome the Vices in combat and standing alone, victorious, they too signify the Church. The row of quatrefoils flanking the Coronation scene contains the heavenly choir of angels, and above them on the left, the angel of the Apocalypse with the eagle of St. John perched on the lectern before him, prefaces a cycle of New Testament scenes. Filling a second row of quatrefoils that stretch across the facade towards the north, they depict episodes in the life of Christ. The New Testament scenes are juxtaposed to the Old Testament narrative cycle that extends to the south on the same level. Together they signify the Old Law and the New. Above, in the frieze at the top of the screen, the resurrected Dead arise from their sarcophagi, and in the summit of the gable, sculptures of the later period complete the program. There Christ (now a modern replacement) sits in majesty above the twelve Apostles and the nine orders of angels. Since the Resurrection frieze contains no imagery referring to the Weighing of the Souls or to the Elect and the Damned, the ensemble consistently refers to the Second Coming of Christ rather than the Last Judgment.

By necessity, reduced in scale and complexity to comply with the spatial requirements of the Salisbury chapter house, the iconographical program presents a shorthand version of the apocalyptic Second Coming at Wells. As in the Wellsian scheme, the Coronation of the Virgin on the west face of the inner door supplies the vital reference to the Church Triumphant signified by Maria Ecclesia, the Bride of Christ--a theme particularly appropriate to a church dedicated to the Virgin. Fortunately, the prerestoration drawing has removed doubts about the subject matter of those lost sculptures. With substitutions and simplifications, all vital elements of the Wells west front appear at Salisbury as follows: in the archivolts enframing the Coronation of the Virgin, fourteen Virtues have overcome the Vices in combat. They too stand for the Church Triumphant. On the eastern face of the inner portal, Christ of the Second Coming and Giver of the New Law sits in majesty surrounded by the symbols of the Evangelists. Below the throne of Christ, an apocalyptic angel swings the golden censer. In the spandrels of the arcades, the Old Testament narrative represents the Old Law in apposition to the sculptures on the doorway equated with the New Law. The tracery in the headings of the windows contained the Keepers and Defenders of that Law--the kings, clerics, and bishops painted on glass who, in their architectural surround stand, as promised, at the gates of the Heavenly Jerusalem.

Even the heraldic shields formerly set into the grisaille of the lancets fit neatly into the program. Six of the shields formerly in the east window and a seventh, presumed to be an invention, now occupy the lowest zone of the three great lancets at the west end of the nave (figs. 13 and 14). Heraldry had also appeared in the decoration at Westminster in the mid-1250s, first in the painted glass of the chapter house and next, in ca. 1265, carved in high relief in the spandrels of the choir aisles to the west of the crossing. Not surprisingly, that colorful and decorative innovation recurred in the Salisbury chapter house, but as part of a much more integrated program than is discernable at Westminster. The heraldry adds new precision to an older iconographical concept. Whereas most of the figures of kings, queens, princes, and warriors at Wells can no longer be identified, and the ecclesiastics and kings in the figurate glass of the chapter house remain anonymous, the noble personages symbolized by the heraldic shields in the Salisbury lancets can still be named, and their actual roles as defenders of the New Law survive in the records of the period. On one occasion or another, most of them for whom shields exist had vowed to take the Cross. Because of the preponderance of crusaders, one writer concluded that the heraldic devices represented a memorial to the eighth crusade. Yet their broader roles as benefactors of the church and defenders of the faith, together with their noble birth and royal kinship, seem more arguable reasons for the armorial representations in the chapter house.

Figure 13

Figure 14

Early drawings again enlarge our knowledge of the original program. Carter's drawings provide evidence of a lost seventh shield that survived until 1802 in the window of the north bay of the chapter house. He labeled it 'imperfect' and noted its 'white gr[ound]' and a blue rampant beast, that he called a blue dragon. In describing the 'invented,' or more accurately, 'composite,' shield in the western lancet of the nave (fig. 15), Winston designated the white ground and blue legs as thirteenth-century fragments of the same date as the chapter house glass, but they are attached to the green body of a sixteenth-century imp. The congruence of the colors can hardly be a coincidence. Clearly the 'composite' device in the nave contains some of the glass from the shield drawn by Carter in 1802. Carter published another shield from the chapter house, the eighth one known. Also, description of two more shields from the Salisbury chapter house survives in the early literature of heraldry. In a manuscript dated 1610 (Brit. Lib. MS. Lansdowne 874), the caption above a row of armorial devices reads: 'These-8-Stand in the windowes of the Chapter House.' Doubtless the plural, 'Windowes,' is correct, for, instead of only eight shields all presumed to have been in one window, the shields pictured in the manuscript raise the known total to ten. An eleventh shield never accounted for in the literature appears in the early nineteenth-century interior view of the chapter house showing the glass in the east window drawn and etched in 1820 for Britton's publication of 1841 (fig. 16). What should have been suspected now becomes obvious. Only a fraction of the shields originally in the chapter house windows has survived. As with the rest of the glass, of a possible sixty-four shields, probably little more than one-eighth remains. Positing two to a lancet as pictured in the nineteenth-century drawing of the east window, we can imagine the brilliance of the armorial devices set into the grisaille to form a continuous band around the octagon.

Figure 15

Figure 16

The influence at Salisbury of the emblems in the Westminster chapter house glass and the twelve shields in the choir aisles of the abbey seems paramount. Seven of the ten known devices from the Salisbury chapter house replicate arms represented in the abbey. That proportion argues for the symbolic character of the chapter house heraldry. Presumably it honored the bearers as noble Defenders of the Faith--their role as Keepers of the Law paralleling that of the kings and warriors of the west front at Wells.

The only element so far unaccounted for in the chapter house program is a reference to the First Coming or Incarnation found both at Wells in the figure of the Virgin and Child above the central door, and at Salisbury on the scrolls of the prophets painted in vaults of the choir. In his article, William Burges hypothesized that figures of the Annunciation occupied two of the niches in the upper arcade which flanks the enframing arch of the inner doorway (fig. 17). If correct, his conjecture completes the program in the Wellsian tradition. But Burges proposed them not as an integral part of an iconographical scheme, but as sculptures inspired by the Annunciation figures in the chapter house at Westminster. (He also made the less likely suggestion that Sts Peter and Paul filled the two remaining empty niches of the arcade. Without the other ten Apostles, the appearance of Peter and Paul in a program representing the apocalyptic Second Coming lacks precedents.) Then, too, they have no place in the iconography of the Annunciation. However plausible Burges's hypothesis, Annunciation figures in the niches cannot be verified from existing evidence. Nevertheless, the program as reconstructed here argues strongly in their favor.

Figure 17

Restoration of Old Testament Scenes

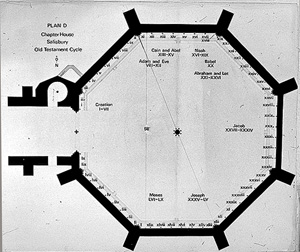

The Old Testament cycle in the spandrels of the blind arcade begins with Creation according to Genesis 1. Starting in the western bay at the right of the inner entrance, the scenes read clockwise around the octagon. The first seven scenes depict the days of Creation (two spandrels in the west bay left of the entrance followed by the first five spandrels in the northwest bay). The next five spandrels contain an Adam and Eve cycle, three in the northwest bay and two in the north bay. The narrative continues with the three main events in the story of Cain and Abel (spandrels three, four, and five), a short Noah cycle of four scenes (last three spandrels and first spandrel in the northeast bay), then the Building of the Tower of Babel (second spandrel) and six incidents in the lives of Abraham and Lot (spandrels three through eight). All eight spandrels of the eastern bay contain a Jacob cycle. Then an unusually long Joseph cycle fills the next twenty-one spandrels (southeast bay, south bay, and the first five spandrels in the southwest bay). The narrative concludes with five episodes in the life of Moses from Exodus (last three spandrels of the southwest bay, and the west bay left of the entrance).

Plan of sculptural cycle

In 1856 a complete restoration of the chapter house was undertaken. Neglected for centuries and its sculpture badly mutilated by iconoclasts during the Civil Wars, the chapter house had become a derelict building that threatened ruin. The chapter commissioned Henry Clutton, a London architect, to take charge of the work. He in turn appointed the London sculptor, John Burnie Philip, to restore the sculptures. Philip then engaged Octavius Hudson, professor of ornamental art at the London School of Design, to redo the polychromy, perhaps the least successful part of the restoration. William Burges, also an architect and at that time a partner in Clutton's firm, published a study identifying each Old Testament scene and detailing all the remaining carving in every spandrel as well as all surviving vestiges of polychromy throughout the building. Hudson failed to follow Burges's notes on the medieval color with somewhat garish results, which elicited in a scathing review in the local press (compare figs. 1 and 2). But before ten years had passed the repainting began to flake, and by the beginning of the twentieth century it had deteriorated to the extent that the chapter ordered its removal (fig. 3).

Figure 1: Northwest bay after Hudson's restoration

Figure 2: Northwest bay today

Figure 3: West bay

Burges, Clutton and Philip were active participants in the Gothic Revival and both had studied and sketched medieval monuments. Philip even organized his London studio of sculptors along the lines of a medieval atelier with sculptors, wood carvers, bronze casters, etc. Several of the carvers from his atelier worked on the spandrel scenes with varying results. In the first three scenes of Creation almost all of the original carving was eliminated, but that practice was halted, and thereafter the damages were repaired with insets of Caen stone into the original spandrel, plus sanding, and re-cutting. An archeological study of the scenes has identified all the surviving thirteenth-century carving, and in the diagram provided here (figs. 4 and 5), the contours of all nineteenth-century insets are outlined. Within those boundaries widely spaced diagonal lines descend from right to left. Repairs made with mastic or mortar are indicated by closely spaced diagonal lines ascending in the opposite direction. Every re-cut or sanded surface is indicated by broken cross-hatched lines, whereas what has survived without any retouching remains unmarked. Additional carving diagrams of Old Testament scenes are available in the image archive.

Figure 4: Sixth Day of Creation, Northwest bay

Figure 5: Diagram of above scene

Thanks to John Carter's sketches, for the most part we can validate the arrangement of the spandrel scenes as restored, though in the least successful work of the restorers the nineteenth-century style prevails and is especially disconcerting throughout in the nineteenth-century heads of the figures (fig. 6, head on the right). As the diagram of Joseph's family bowing before him shows, the restorer responsible for some of the Joseph cycle often was overzealous in sanding and re-cutting (figs. 7 and 8). Pre-restoration engravings that had been published, such as the view of the Pharoah's dream published by John Britton in 1814 (fig. 9) and the scene of Joseph's brothers in Egypt published by William Dodsworth the same year (fig. 10), coupled with unpublished drawings in various London archives provided further resources that assisted in authenticating the scenes as restored.

Figure 6: Drunkenness of Noah, northeast bay

Figure 7: Spandrel IV, southwest bay

Figure 8: Diagram of above scene

Figure 9: Spandrel III, south bay

Figure 10: Spandrel VII, south bay

List of Old Testament Scenes

N.B. For detail views of the Old Testament scenes, visit the image archive, under List of Interior Images, subsection Chapter HousePolychromy

Any attempt to reconstruct the Salisbury chapter house as it appeared in the thirteenth century must recreate its original polychromed splendor in the mind's eye. William Burges's monograph provides the most reliable and complete information about the colors that were still visible before the mid-nineteenth-century restoration began. In the absence of any record of an earlier repainting, his assumption that he was looking at the original color seems valid. Knowing that the restoration would destroy all vestiges, he noted and described the color wherever it occurred:

"The colour began with the tile pavement, which was divided from the walls by the white colour of the stone benches. Then came the arcade richly coloured, the Purbeck columns dividing a series of curtains painted upon the walls. The colours of these last are very doubtful; but the most probable...pink, diapered, edged with yellow, and lined with green. The caps of columns are gold, pricked out with colour. The abaci are in Purbeck marble. The colours of the mouldings of the arcades are counter-changed in each bay. The principal ones were powdered with various patterns, such as lions, fleur-de-lys, the heraldic cinqfoil, &c. The space within the arches had the name of the prebend inscribed in a square frame within a circle, while the spandrels were filled in with the polychromed sculptures....It will be perceived that the greatest amount of colour is in the arcade; from this it is carried up to the groining by means of (1) the coloured parts of the grisaille glass; (2) the Purbeck shafts of the mullions and jambs; and (3) a red fillet on the principal mouldings.

The ribs of the vaulting have their mouldings divided by red hollows and fillets; and a nebule ornament of the same colour occurs at the sides. The main body of the vaulting is covered with red lines, not unlike imitation stone work. The bosses are gilt, relieved with red, and on each of the three sides is painted a mass of green and yellow foliage on a triangular dark red ground."

Figure 1: G.F. Sargent's 1852 watercolor, one of few views of the chapter house before restoration, offers some evidence of color. (Collection of the Salisbury and Wiltshire Museum)

Even the black and white photographs showing the nineteenth-century repainting suggest the concentration of color in the floor tiles (fig. 2). The original were red and black with patterns inlaid in white pipe clay yellowed by the glaze (figs. 3 and 4).

Figure 2

Figure 3

Figure 4

The eye moves up from the dense color of the floor to the rich polychromy of the arcade, then to the translucent coloring of the grisaille of the windows above, and finally, to touches of color accenting the ribs, red outlines simulating masonry joints, color on the vaulting bosses, and painted designs surrounding them (figs. 5 and 6).

Figure 5

Figure 6

The arcades of the bays must have rivaled illuminated manuscripts in brilliance. In fact, the treatment of the arches of the arcade with 'powdering' of various patterns such as fleurs-de-lys and heraldic cinquefoils strongly suggests the influence of manuscripts. In the spandrel scenes, here and there, additional painted trees and houses originally filled in the blank spaces between the scenes at the apex of the arches.

The nineteenth-century painter, Octavius Hudson, interpreting remnants of the polychromy in one of the scenes of Creation as vestiges of diapering, undertook to diaper the background planes. Forming hexagonal compartments, his diapering bore an unfortunate resemblance to mosaic bathroom tiles (fig. 7). But, as the photographs show, where there is no diapering, and where he also failed to reproduce the thirteenth-century painted architectural and foliate details observed by Burges, the scenes lack cohesion (fig. 8). Then, too, the polychromed figures and carved vegetation appear spindly and too sparse. Certainly with the original polychromy, diapering, gilding, and painted glass, the Salisbury chapter house must have seemed like a jewel box emulating the splendor of the chapter house at Westminster which had enjoyed the munificent, royal patronage of Henry III.

Figure 7