Cathedral Schools and Chantry Colleges at Salisbury

Cathedral Schools

When the Roman Empire collapsed, formal education in Western Europe collapsed with it. Most of the few schools that managed to survive were connected with monasteries. The monasteries did good service in keeping learning alive and in preserving libraries, but their schools were intended for monks, and were inaccessible to most people. What education that did occur was normally personal and informal. Parents passed on knowledge to their children, and masters taught their apprentices skills. If a parish priest were able to read he might offer classes for boys in his parish.

Salisbury Cathedral and Bishop's Palace (the present Cathedral School) from the southeast.

Under the rule of the Carolingian emperor Charlemagne (d. 814) there was a revival of interest in education. Charlemagne needed educated men to serve his empire, and so he made it a policy to promote learning. About the same time there was an increasing concern in the Church to provide education for priests to help them carry out their duties.

Charlemagne attempted to settle the problem of education by ordering bishops to set up schools at their cathedrals. One of his laws from 789 ordered "In every bishop's see ... instruction shall be given in the psalms, musical notation, chant, the computation of years and seasons, and in grammar; all books used shall be carefully corrected."

Cathedral schools never existed at every cathedral, but many cathedrals did become centers of what we would call elementary education. Bishops who wanted to encourage learning could appoint a schoolmaster, if they could find someone qualified. Education was often based on old Roman texts, and over time tended to divide into a concentration on music (which prepared boys for service in the cathedral liturgy) and on grammar and rhetoric (which prepared boys to serve as parish priests or in the church bureaucracy).

There are few records of early cathedral schools, since the emphasis was on education and not degrees. Often the schools were not permanent, being forced to close when a schoolmaster could not be found. At other cathedrals, such as Paris, schools attracted scholars and teachers, and eventually became the nucleus of universities.

Salisbury was famous for education from relatively early times. The twelfth century English historian John of Salisbury was the most renowned product of Salisbury's cathedral school. A century later Robert Grosseteste, a scholar with Salisbury connections and a bishop of Lincoln, wrote about the school at Salisbury and its schoolmaster, a 'Magister Jordanus.' Modern Salisbury still hosts a school connected with the cathedral, carrying on a tradition of education at least eight hundred years old.

The University at Salisbury

In the Middle Ages universities were generally not founded but grew up when distinguished teachers drew students to a certain place. As the number of students and teachers became larger, steps would be taken to organize teaching, and eventually to grant degrees. And so a university would be born.

In the thirteenth century it appeared that a university might grow up at Salisbury. The cathedral town was already recognized as a center of learning, and was associated with many respected scholars and educators. The Bishop St. Osmund had fostered a reputation for learning in Salisbury, a reputation which grew during the time of Bishop Richard Poore, and the rapid spread of Salisbury's 'Sarum Rite' as the most common form of liturgy in England enhanced the prestige of the cathedral city. Salisbury's cathedral school also boasted a successful alumnus, the English historian John of Salisbury.

Salisbury also gained in reputation through its association with several educators; two of the most respected teachers in thirteen century England were at one time canons at Salisbury Cathedral. One was Edmund Rich, who in between serving as the first official lecturer in theology at Oxford and as archbishop of Canterbury was cathedral treasurer at Salisbury. He was known for the great affection he had for his students, and for his pious life. He was canonized as St. Edmund in 1248. The other great teacher was Robert Grosseteste, also an Oxford professor, and later bishop of Lincoln. Grosseteste was renowned as a preacher, and many of the Franciscan friars who studied under him at Oxford became well-known for their preaching. Grosseteste was also a scholar of reputation, who wrote authoritatively on many subjects. Like Edmund Rich he was a man of great personal piety. Several efforts were made to canonize him, though he never officially became a saint. While neither Rich nor Grosseteste taught at Salisbury, the association with the cathedral of their learning and their piety enhanced Salisbury's prestige.

Common seal of St. Edmund's. St. Edmund is represented under the canopy.*

A number of other respected scholars and teachers were connected with Salisbury, and their presence, along with the successful cathedral school and Salisbury's reputation for learning proved attractive to students. Thus, when a number of Oxford students sought a new place to continue their studies, Salisbury was a natural choice.

Medieval universities often had their start when students from an established university migrated in groups to a new location to study under better conditions. Oxford University had its origins in a student migration from the University of Paris in 1167.

A number of student migrations from Oxford nearly created a university at Salisbury. In 1209 an Oxford woman was killed by students, and in return three students were lynched by a mob. Subsequently, many students left Oxford. Some went to Cambridge, where a university soon grew up. Others went to Paris. Though it is not certain, it appears that some made their way to Salisbury.

In 1238 a new set of disturbances drove students from Oxford. On this occasion a fight broke out in a kitchen between students and members of the Papal legate's entourage. The legate's brother was killed, and the legate, a Cardinal Otho, was forced to barricade himself in a tower, then flee Oxford in the middle of the night. When order was restored many students made their way to other cities. Salisbury received a number of these refugees, who provided the foundation of the student body.

The students at Salisbury were under the supervision of the cathedral chancellor. This was a common arrangement at universities connected with cathedrals, but particularly appropriate at Salisbury, where a number of chancellors were known for their learning. The chancellor made arrangements for members of the cathedral staff to teach classes, and also brought in visiting lecturers. In addition, classes were offered by some of the Dominican friars in Salisbury. Students studied theology and liberal arts, meeting for classes in the cathedral close. Though the cathedral had a library, a new library was built for students, including classrooms with desks.

Seal of Adam the Chancellor, Salisbury, 1238*

Seal of Chancellor Simon de Mechum, Salisbury, 1285.* Note that both chancellors are portrayed seated at lecterns reading texts.

Several bishops of Salisbury made an effort to support the university. Bishop Giles of Brideport established De Vaux College to provide housing and scholarships for twenty poor students. Another bishop, Walter de la Wyle, endowed the College of St. Edmund in part to provide stipends for graduate students or teachers.

Courses were offered in Salisbury as late as 1360, but the shadow of nearby Oxford (only forty miles away) prevented a true university from emerging. Eventually most students returned to Oxford. De Vaux College remained in Salisbury. Its students divided their time, spending part of the year studying at Oxford, and part in Salisbury. A new education facility was built on cathedral grounds for them in 1445, and teaching continued to be offered until 1545, when De Vaux College was dissolved and annexed by the English crown.

*Seals from Benson and Hatcher, The History of Modern Wiltshire: Old and New Sarum, or Salisbury, vol. 6. London, 1843.Medieval Colleges

Modern Americans tend to think of colleges as academic institutions. Yet even today the word 'college' is used in a variety of ways. Every four years the Electoral College chooses the president of the United States, while a new pope is chosen by the College of Cardinals. The College of Arts and Sciences at a large university is not the same as a small liberal arts college.

Medieval people used the term 'college' in a number of different ways, all of which are reflected in the definition of the word supplied by the Oxford English Dictionary: an organized society of persons performing certain common functions and possessing special rights and privileges.

One common type of medieval college was the association, guild, or club. Such a college would consist of a group of people joined together in a more-or-less self-governing society. The most familiar example of this sort is the College of Cardinals, which was created in the Middle Ages.

A second type of medieval college was the religious college. This college would consist of a community of priests who lived together under a superior. The college might exist to provide prayers and masses for an individual or a group, to allow devout Christians to live in a religious community, or to provide the necessary staff for grand services of worship at a large church. The College of St. Edmund, connected with a parish church and charged with celebrating daily masses for the founder and benefactors of the college, is an example of this type.

Detail from 1616 map by John Speed, showing St. Edmund's parish church and residential building.

A third type of medieval college was established to provide a community for churchmen loosely associated with cathedrals or other large churches. The musicians and chantry priests at such places were often poorly paid and poorly disciplined, and were liable to create disturbances and behave inappropriately. A college provided the musicians (called vicars choral) and priests with food, housing, and a community, while providing the cathedral with a way to monitor and control behavior.

The most familiar type of medieval college, the academic college, grew out of the kinds of colleges listed above. Academic colleges were expected to keep students under control, and most college founders required that college members pray for the founder. Members of colleges had certain privileges and formed a close association with one another. De Vaux College is an example of this kind of institution.

Why Found a College?

People in the Middle Ages had a great many motivations for philanthropy, but the most significant motivation for charitable giving was the hope of obtaining spiritual benefit from God for good works. Catholic doctrine taught that the sacraments of the Church (such as baptism and the mass) wiped away the stain of original sin, but left the necessity of making satisfaction to avoid punishment. This satisfaction could be made in this life through repentance and good works, or by suffering in purgatory after death. For those who hoped to earn God's favor by charitable giving, a college offered the advantage of providing two opportunities to benefit spiritually. In the first place, a college dedicated to a worthy cause was itself a good work, and would count in its founder's favor in the eyes of God. But in addition, there were the prayers of the members of the college, prayers which would also serve to benefit the college founder. The canons at the College of St. Edmund were to see to it that a mass was performed daily on behalf of the soul of their patron, Bishop Walter de la Wyle.

A second motivation for people in the Middle Ages to use their money to benefit others came from the expectation that the wealthy and the powerful would act as benefactors to those in their communities. When Bishops Giles of Brideport and Walter de la Wyle established their colleges they were aiding the community in a number of ways. By providing support for students and teachers the two men were encouraging the growth of a university at Salisbury. In addition, they were providing opportunities for poor students to get an education. The people of Salisbury gained from having potentially unruly students kept off the streets and under strict control. The beautiful liturgy at Salisbury Cathedral was enhanced by the presence of members of the two colleges in processions. The College of St. Edmund provided parish services for inhabitants of a rapidly growing town. Through their colleges the two bishops were able to fulfill social expectations to act as patrons to their cathedral and to their cathedral city.

Just as in modern times, medieval people also established charitable institutions as monuments to themselves. A great establishment could be a memorial to its founder, and the temptation to create such memorials may have been particularly strong for bishops, whose careers could bring great wealth but also limited the opportunities to pass the wealth along to heirs.

Personal interest also played a role in charity. Bishop Giles was a university graduate, and the elaborate carvings of university scenes on his tomb suggest he was enthusiastic about education. De Vaux College may be a testimony to the bishop's commitment to higher learning.

Financing a College

Creating new institutions in the Middle Ages was as expensive and challenging as it is today. Medieval benefactors did not have the luxury of using stocks, bonds, and savings accounts to provide money for their projects. Instead they relied on a variety of strategies to ensure that their foundation would have sufficient funds to continue for many years.

The most common way to endow an institution was to use land or buildings that would provide a regular source of revenue. A field, for instance, might be given to a college, allowing the college priests to farm the land themselves or to rent it out at a profit. Either way, the land ensured a source of income. In the same way a building, such as a house or a shop, could guarantee rental income in the future. When large gifts of land and buildings to non-profit organizations started to become common, the English government began to worry about the potential loss of tax revenue. As a result Parliament passed the Law of Mortmain in 1279, which made it necessary to get a licence in order to give property to a charitable institution. There was a high fee for the licence, which was intended to compensate the government for lost tax revenues from the property. Careful records of all proposed gifts were kept by the government after 1279, and these records have proved invaluable to historians studying medieval England.

A second common way to endow an institution was to provide it with some other regular form of income. A parish church, for instance, had an income from its lands, from the tithes owed by members of the parish, and from payments for various religious services performed throughout the year. Out of this income had to be paid certain expenses, such as the salary of the parish priest, supplies for the church, and maintenance for part of the church building. After all the expenses were paid, there was often money left over. A wealthy donor might secure the right for his or her college to keep the extra income from a parish church. The College of St. Edmund, serving the parish church of St. Edmund, had the right to the parish's revenue. The College could hire a priest (known as a vicar) to serve the parish, or save the money by having members of the college do the work. Sometimes, though, a patron could secure revenues from parishes that had no connection with the college. Eventually the College of St. Edmund earned the right to keep the profits from several other churches.

St. Edmund's parish boundaries, overlaid on 1857 map of Salisbury

A college founder could endow his institution with property to provide future income for the institution, and he could make cash donations to pay for needed buildings and supplies. But there was always the possibility that a college's endowment might not be adequate to cope with future expenses. For that reason college founders often made an effort to encourage others to donate money to their colleges.

One common strategy was to offer benefactors an opportunity to share in the spiritual benefits provided by the prayers and masses of college priests. Walter de la Wyle had the priests at his College of St. Edmund perform a daily mass on behalf of college benefactors. Anyone who supported the college (or, perhaps, supported the college significantly) could be included in the prayers of the college's priests.

A college founder might also hope that his friends and family would continue to support the college in later years. It was not uncommon for descendants to continue to give money to a college an ancestor had founded even a hundred or more years after the founder's death. In addition, those who had benefited from a college might also someday be in a position to provide financial support for the college. One of the poor students who studied at Salisbury on scholarship at De Vaux College, for instance, went on to make his fortune, and over the years made a number of large gifts to the community that had given him his start.

Colleges that were strapped for cash after the death of their founders also had opportunities to bring in revenue. A common way was to make an arrangement with an individual who wanted perpetual prayers said for his soul after his death. In return for some sort of payment, the college would agree to provide a priest to say masses and prayers for the donor. (The provision of a priest to say prayers for the soul of a dead person is known as a chantry.) At St. Edmund several chantries were created in the years following Bishop Walter's death. While this practice did provide needed income for institutions it had its dangers as well. Often the gift which established the chantry was quickly spent, or was poorly invested, in which case the college was still obligated to carry out the intercessory rites on behalf of the patron. If the gift was no longer adequate to cover the salary of the priest saying the prayers then the college had to provide the balance from its own resources. In the long run chantry obligations often hurt the financial standing of an institution more than they helped.

Another option for colleges in financial difficulties was to gain the right to hold certain fund-raisers. The College of St. Edmund was awarded the right to hold an annual fair, using the proceeds to support the work of the College.

De Vaux College

Shortly before he died Bishop Giles of Brideport founded a college in Salisbury to support poor students. The college was built near the hospital of St. Nicholas, and was named 'The House of the Valley of Scholars of Blessed Nicholas.' The name was adopted from a college at the University of Paris, and was quickly shortened from the original Latin 'Domus Vallis Scholarium' to 'De Vaux.'

Current view of De Vaux Place, where college was formerly located

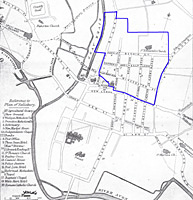

Location of De Vaux College represented in blue, on 1857 map of Salisbury

Giles intended the college to consist of three priests and twenty poor scholars. One of the three priests was, as warden, to be in charge of the college, and all wardens were required to be canons of Salisbury Cathedral. The cathedral chapter was to have ultimate supervision over the college.

When De Vaux college was founded in 1262 there were many students in Salisbury, and it appeared that a true university might grow up there. The university never developed, and within a hundred years most Salisbury students had made their way to nearby Oxford. De Vaux college, however, remained in Salisbury, though eventually most of the members of the college came to spend part of the year at Oxford. It is known that some fellows of the college went on to receive degrees in theology, medicine, civil law, and canon law, and a few even earned doctorates in theology and medicine.

Institutions like De Vaux were expensive, and it appears that there was rarely enough money to completely fulfill Bishop Giles' hopes for the college. Usually the college supported about a dozen students at a time. Most students gave up their fellowship at the college when they received a degree and were able to get good jobs, but a few stayed on at the college for years.

De Vaux continued to support poor students and to arrange for classes until 1542 when it was seized by the crown as part of the Dissolution of Religious Houses. All of the students at that time, save one, were given pensions in exchange for losing their college stipend. The college then ceased to exist, and the buildings were sold. Most of the college buildings were demolished between 1834 and 1836 to make way for new houses on the site. The area of the old college is still known as 'De Vaux Place.'

Giles of Brideport, bishop of Salisbury

Giles of Brideport (or Bridport) was born in Bridport, Dorset around the year 1200. Very little is known about his early life. He apparently received a university degree, probably from the university of Paris. The first record of his career dates from 1238, when he was serving as Archdeacon of Berkshire, an important administrative post with a responsibility for overseeing the conduct of priests within the region. Offices with more responsibility and more profit followed, including being elected the Dean of Wells Cathedral in 1253.

Effigy of Giles of Brideport

Tomb of Giles de Brideport, in south choir aisle. Tomb is at right, near entrance to southeast transept.

William of York, bishop of Salisbury, died in 1257, and it was then that Giles achieved his highest post. Elected bishop by the cathedral chapter and confirmed by King Henry III, he was consecrated bishop of Salisbury on March 11, 1257. He quickly became a valuable civil servant for the English monarch. He was sent to Rome as part of a special mission to negotiate a claim on the throne of Sicily with the pope on behalf of Henry III's son Edmund. As a reward for the way in which he carried out his mission Giles was rewarded with permission to retain a number of lower offices a bishop would normally have had to give up. Such pluralism (as the holding of numerous ecclesiastical offices is technically known) allowed him to become a rich man; he would use his wealth for a number of charitable enterprises. Giles continued in his service to the English government. He was appointed to a reform commission by Parliament, and later was chosen to arbitrate a quarrel between the king and the barons.

But although Giles was active serving the king, he did not neglect his diocese. During his time as bishop the present cathedral of Salisbury was completed and consecrated, the cathedral's new lead roof having been donated by Giles himself. The consecration of the cathedral was marked by a great celebration which was attended by the king and queen, two of their sons, and numerous nobles and bishops. He also convoked a Synod of the clergy in his diocese in an attempt to reform and improve the ministry of local priests. A similar attempt to carry out reforms of the cathedral chapter met with a firm rebuff from canons jealous to guard their independence. The bishop also founded De Vaux College near the cathedral to support poor students.

Giles of Brideport died on December 13, 1262 and was buried in the cathedral, where his tomb can still be seen. His brother, Simon of Brideport, was buried alongside him.

The Tomb of Giles de Bridport

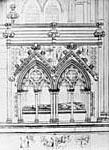

The tomb of Giles de Bridport,* bishop of Salisbury from 1256 to 1262, stands on a plinth between the south choir aisle and the eastern chapels of the southeast transept of Salisbury Cathedral. Made of white Chilmark stone with Purbeck marble details, the tomb is designed as a miniature building enclosing the effigy of the bishop behind open arcades and within a chamber consisting of two rib-vaulted bays.

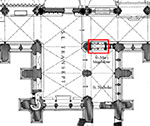

Plan, southeast transept, tomb marked in red

North view of tomb, taken from south choir aisle

The earliest representation of the tomb is an etching by John Carter who was employed by Richard Gough, president of the Society of antiquaries in London, to journey to Salisbury and make drawings of sepulchral monuments. Gough published the etching in his Sepulchral Monuments, 1786, 1796. The next representation is by C.A. Stothard whose drawing was engraved and published in William Dodsworth's Historical Account in 1814. Both depict the tomb from the north, or aisle side, and include small sketches of the scenes on the south, or chapel side of the tomb.

Carter etching, north side**

Stothard engraving, north side***

The tomb canopy is unusual because of the sculptural scenes which depict, in a very general way, events in the life of the bishop. Among the scenes on the chapel side of the tomb are two depicting a school master and students. In one, a youth (perhaps Giles himself) seated cross-legged at the feet of a larger figure in secular dress. The scenes are very damaged, but the relationship of the two figures is typical of the learning situation in medieval times. The master sat in a chair (cathedra in Latin) and students sat or stood to listen. The second scene shows a master, seated with a lectern, and a group of students before him. Here I suggest the master is Giles, who, in his course of study toward the degree of Master of Arts at the University of Paris, must practice teaching.

South view of tomb from southeast transept

Tomb scene

Tomb scene

Tomb scene

A third scene on the chapel side of the tomb shows two figures in secular dress, the one on the right, I suggest, is Giles receiving his degree. A shield hangs in a tree adjacent to this figure. The shield was once painted with the arms of Giles de Bridport: Azure, a cross between four bezants, Or.

*For more information on this tomb see: Marion E. Roberts, "The Tomb of Giles de Bridport in Salisbury Cathedral," The Art Bulletin, LXV (1983), 659-586. **For Carter's etching, see: Richard Gough, Sepulchral Monuments in Great Britain, 2 vols. London, 1786, 1796. Carter's etching is in vol. 2. ***For Stothard's engraving, see: William Dodsworth, An Historical Account of the Episcopal See and Cathedral Church of Sarum or Salisbury, London, 1814.The College of St. Edmund

The College of St. Edmund was founded in 1268 by Walter de la Wyle, bishop of Salisbury. The college was named in honor of Edmund Rich, archbishop of Canterbury and one-time treasurer of Salisbury Cathedral, whose pious life and reputation as archbishop led to his canonization in 1248, only eight years after his death.

Common seal of St. Edmund's. Edmund Rich, or St. Edmund, is represented under the canopy.*

1616 map of Salisbury by John Speed. St. Edmund's church and residential college are outlined in blue.

The College was meant to serve a new parish church, named in honor of St. Edmund, in the rapidly growing town of Salisbury. Bishop Walter's foundation charter sets out the boundaries of the new parish. The College was to consist of thirteen priests, one of whom was to serve as 'provost,' or head of the college. The priests were meant to share a common life. They were required to eat their meals together in the college refectory, and to sleep in the same dormitory; a priest who was ill could receive permission to eat or sleep privately. The priests were expected to wear similar clothing.

The priests were required to take part in certain processions at the Cathedral, and also to participate in religious observances at the Church of St. Edmund. In addition to the standard rites expected of every priest, the canons (as priests at a college were known) were required to celebrate the hours of the Blessed Virgin Mary, and each was also responsible for celebrating a particular mass. One priest was to celebrate mass on behalf of the soul of the founder, another to benefit benefactors of the college. All the other priests were to say masses for the dead.

As well as attending to religious duties, the priests of the college were expected to participate in the life of the university which was growing up in Salisbury at that time. Every morning after matins and hearing mass they were required to attend lectures.

Bishop Walter left the power of disciplining, and if necessary removing, the college canons to future bishops of Salisbury. Should the need for disciplinary action arise between the death of a bishop and the appointment of his successor, the cathedral chapter was authorized to take appropriate action. The provost was responsible for running the college under ordinary circumstances, and was charged with carrying out day to day business.

Bishop Walter had left the control of every-day affairs at his college in the hands of the college provost, but had wisely made arrangements to allow the bishop of Salisbury to intervene should serious difficulties arise. Such difficulties had arisen by 1294, when Bishop Nicholas Longespee was forced to remind the college canons to obey the provost and to abide by the residency requirements. In 1319 another bishop called the canons to account for failing to participate in religious processions at the cathedral. But aside from these two incidents the college appeared to function as intended for many years.

The College of St. Edmund was created to serve a new parish. The College received the income from the parish of St. Edmund, and in return was responsible for seeing that parish ministry was carried out. It is not known if the canons did the parochial work themselves, or hired a vicar to fill the position. In addition to providing for cure of souls in the parish, the College was also obligated to use some of the parish income for the upkeep of the parish church. At least one major refurbishment program was carried out in the fourteenth century.

St. Edmund's Church. The church building was subject to many alterations in later centuries.

In addition to parochial responsibilities and meeting the requirements made by Bishop Walter, the canons at St. Edmund undertook other religious obligations. To help raise money for the institution several chantries were established at St. Edmund's, where in return for a large gift the college agreed to have a priest say prayers and perform masses every day for the soul of the donor. In addition, the income of a nearby parish church, St. Martin's, was given to the college, and in exchange the provost of St. Edmund's was required to serve as parish priest there, or hire a vicar as replacement.

St. Edmund's Church

Beginning in the 1530s St. Edmund's was plagued by discipline problems, financial mismanagement, scandal, and poverty. The College continued until 1543, when it was dissolved as part of the Dissolution of Religious Houses carried out by Henry VIII. The College buildings were sold, but St. Edmund's continued to serve as a parish church for the next four hundred years. It was finally desacralized in 1973, and now serves the community as an Arts Centre.

*Seal from Benson and Hatcher, The History of Modern Wiltshire: Old and New Sarum, or Salisbury, vol. 6. London, 1843.Walter de la Wyle, bishop of Salisbury

At a time when government service or an academic career were the two most common paths to promotion within the Church, Walter de la Wyle, bishop of Salisbury (1263-1271), provides the rare example of an individual who worked his way up through the ranks in one diocese. Walter began his career as a chaplain to Robert Bingham, bishop of Salisbury from 1229-1246. Bingham, who had a reputation as a scholar, must have thought highly of Walter since he appears to have acted as his patron. He was probably responsible for Walter's appointment as warden of a bridge over the Avon connected with St. John's Hospital. Eventually Walter was elected Succentor of Salisbury. The Succentor was one of the chief officers of a cathedral chapter, with responsibility for overseeing religious ritual in cathedral worship services. This was a responsible and prestigious position at any cathedral, but especially so at Salisbury, since the 'Sarum Rite,' the order of service used at Salisbury Cathedral, was quickly becoming the most popular order of service in England. It was from the office of Succentor that Walter was elevated to the office of bishop in 1263 as the successor to Bishop Giles of Bridport.

Effigy of Bishop Wyle

Wyle effigy and tomb chest, presently located in the nave under the south arcade in bay 14.

Walter's most enduring legacy as bishop was the founding of St. Edmund's College and the creation of a new parish of St. Edmund's to serve the growing population of Salisbury. The College was also meant to help support the growing university at Salisbury.